Terminology Management 1

Part 1: Some Whys and Whats

If a spreadsheet is not enough and a term base is too much

After two years as a lone technical writer in an office full of software developers, I sometimes just let the flood of abbreviations and acronyms, wayward spelling variants, synonyms and polysemes wash over me and decide that it is safe to assume that these people do indeed know what they are talking about, even if nobody else does.

Sometimes however, I cannot help but remember that it is my job to regulate this linguistic flood and make sure that the customers and developers cannot only agree on the wording of a specification but also on what this wording is supposed to mean, or that the users do not click the ‘Create template’ button to have the ‘Create pattern’ dialog pop up.

Because that’s what terminology management does! It puts the focus on your ideas and tries to help you find the right words for these ideas and use them consistently.

Requirements from the technical writer’s point of view

A term collection should be ordered by concept, treating all information concerning the same idea as a unit. This includes a definition and any number of terms which may belong to multiple languages. Linguistic purists would argue for a definition for each language as concepts differ between cultures, but I decided to go forward with just one definition in German.

There are a number of additional elements that should be included to provide enough information for a decision on which term to use.

- Semantic clarification is provided by the definition — this tells you which concept a term stands for.

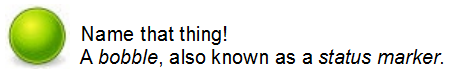

- Pragmatic information provides clues as to what context the term can be used in. In our term base, each term can be assigned to specific software products and to customers. An example phrase can also be added to clarify the context of a term’s usage or to provide a typical collocation. Terms can be marked with a status in order to be able to maintain terms that have been changed or that do no longer apply. It is also useful to explicitly include a status for ‘forbidden’ terms to make them accessible and to inform your colleagues that these terms have fallen from favor. For example, one could search for ‘bobble’ and learn that a little spherical-looking graphical element in traffic-light colors is supposed to be called a ‘status marker’.

- Syntactic information can be reduced to just giving the part of speech and, in German, the grammatical gender. This last can actually be helpful for Germans because some nouns can take more than one gender, and we want to always use one of them for consistency.

Once you have painstakingly collected all this information for a number of terms, you can start to worry about how people are actually going to access this information. Likely the most important feature of a term base is that it is searchable — at a minimum, you want to search for terms and also be informed when they occur in a definition. If you maintain pragmatic information, you will also want to search this, for example, find all terms that are specific to a certain customer’s version of product X. Ideally, the information should be provided in a way that is easy to integrate with the habits of the non-linguists in your organization.

Typical solutions

To be brutally honest, most translators and technical writers just keep word lists in a spreadsheet program. It’s not really what those programs were made for, but this can still work out OK for not-too-large collections and a not-too-large number of users.

I did not expect the spreadsheet solution to work out OK for me because I have seen too many spreadsheets floating in the limbo of shared network folders in uncountable personal versions — we’re just too many people for this. Also, a spreadsheet makes it hard to maintain an entry structure that has more than, say, two or three terms and a definition.

Of course, there are any number of terminology management systems available commercially. The trouble for my superiors is that these do not come for free, not even the read-only licenses. The trouble for me is that these systems are large and unwieldy, consisting to a large part of functionality I do not require. The entry structure for each concept can often be freely configured, no complaints there. However, the issue that makes me personally feel squeamish about starting with one of the market-leading systems is that I do not want to keep all my terminology data in some proprietary database format. You may call me paranoid, but I do feel better with my data in text files, human-readable and version-managed. I have to mention here that terminology management systems usually offer an export function to the XML-based terminology exchange format TBX, but this is not their native storage format.

The way forward

I did get a lightweight, customized, open-source solution because I’m married to an IT consultant whose job it is to make other people’s jobs easier. What we decided on was an editor for Eclipse that would provide comfortable editing for my terminology text files, including templates, autocomplete, validation, syntax highlighting and folding.

In a follow-up blog post, we’re going to present the key features of the Xtext terminology editor for Eclipse, its export functions and research options provided to the developers I work with.